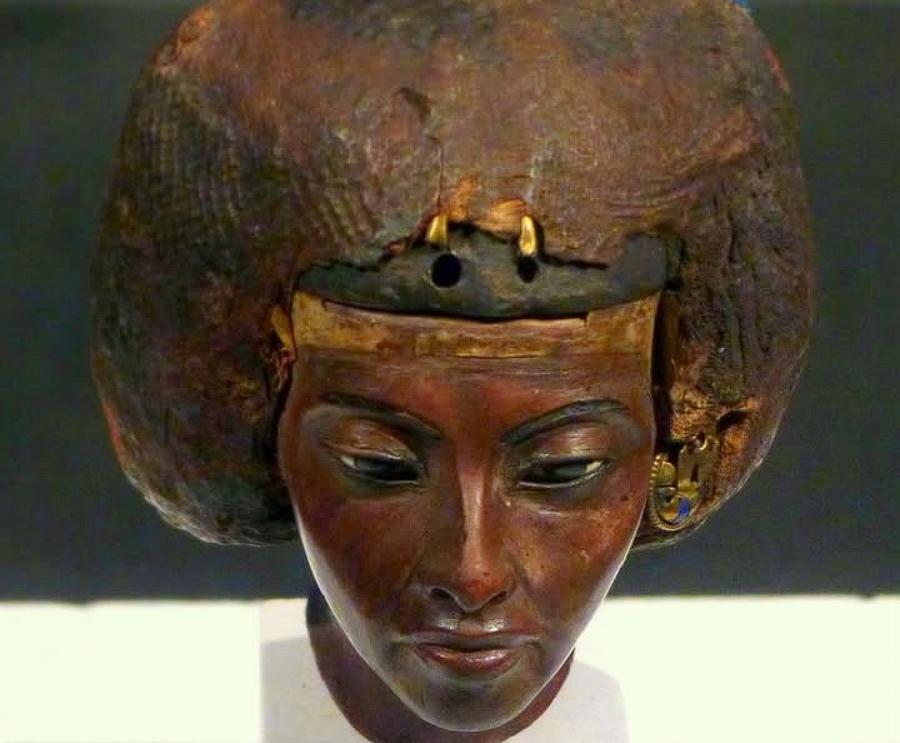

Yew wood, with its rich grain and enduring strength; gleaming silver, a symbol of purity and status; radiant gold, the metal of gods and royalty; vibrant faïence, shimmering with an otherworldly blue; and humble linen, the fabric of both life and the afterlife—each material in this tiny yet undeniably regal portrait of Queen Tiye whispers a distinct story. Woven together with meticulous artistry, they coalesce to speak volumes of power, asserted divinity, and the enduring force of royal memory in the annals of ancient Egypt.

This remarkable head of Queen Tiye, skillfully carved from yew wood during the twilight years of her husband Amenhotep III’s long and prosperous reign (circa 1391–1353 B.C.), stands as one of the most intimate, compelling, and surprisingly human representations of a royal woman to have survived from the vast landscape of ancient Egypt. Unearthed at the archaeological site of Medinet el-Gurob and now carefully preserved within the esteemed collections of the Neues Museum in Berlin (catalogued as ÄM 21834 and ÄM 17852), the yew wood head itself measures a mere 5 centimeters in height. Yet, when reunited with its long-lost and equally magnificent crown—a headdress resplendent with a central sun disc, the protective and maternal cow horns of the goddess Hathor, and the tall, elegant double plumes also associated with this powerful deity—the full, reconstructed piece rises to an impressive 22.5 centimeters, a testament to the queen’s elevated status.

Unveiling Hidden Layers: Silver, Gold, and the Evolution of a Royal Image

What renders this particular sculpture even more intellectually fascinating and historically significant is the intriguing narrative that lies concealed beneath its readily visible surface. Cutting-edge CT scanning technology, employed by modern researchers, has unveiled the remarkable secret that the original headdress adorning Queen Tiye was not the feathered solar crown we see today. Instead, it was a traditional silver nemes headdress, the iconic striped headcloth worn by pharaohs as a symbol of their royal authority, complete with a majestic golden uraeus, the rearing cobra emblem that represented royal protection and divine legitimacy. This regal and distinctly pharaonic headgear was subsequently and deliberately wrapped in layers of fine linen, meticulously adorned with numerous vibrant faïence beads of a characteristic Egyptian blue hue, carefully arranged to create the soft, rounded appearance of the headdress that is now visible. Though the majority of these once-brilliant blue beads have been lost to the relentless passage of time, a poignant few stubbornly remain at the back of the head, like ghostly and ethereal echoes of the statue’s former, perhaps more overtly regal, brilliance.

A Bold Statement of Divinity: Akhenaten’s Elevation of His Mother

However, the most profound and politically charged layer of meaning embedded within this extraordinary piece is undeniably symbolic, a deliberate act of elevation orchestrated by Tiye’s revolutionary son, Akhenaten. By the seemingly unprecedented act of adding the distinctly feathered solar crown traditionally associated with the powerful goddess Hathor to his mother’s already iconic image, Akhenaten effectively elevated Queen Tiye into the realm of the divine—a bold and unprecedented gesture that occurred not posthumously, as was customary for deceased royalty, but while his mother was still very much alive and wielding considerable influence. This audacious act was not merely a personal tribute; it was a calculated political and religious gesture, entirely in keeping with the radical and transformative spirit that defined Akhenaten’s tumultuous and ultimately short-lived reign, challenging long-established religious norms and asserting a new, more centralized form of worship.

A Reunion in Berlin: Completing a Queen’s Multilayered Legacy

The remarkable rediscovery of the long-separated crown in Berlin after years of being considered lost completes not only the physical reconstruction of this extraordinary statue but also significantly enriches the narrative of a queen whose enduring legacy, much like her multifaceted portrait, was both exceptionally powerful and richly multilayered. Queen Tiye, as revealed through this small yet potent image, was not simply the Great Royal Wife of a powerful pharaoh; she was a formidable figure in her own right, a woman who navigated the complex political and religious landscape of her time with intelligence and influence, and whose son, in a testament to her enduring power, sought to elevate her to a divine status that transcended the traditional roles of even the most powerful royal women in ancient Egypt. Her portrait, now reunited, stands as a compelling symbol of her enduring impact and the revolutionary era in which she lived and thrived.

CÁC TIN KHÁC

Mary Walton: The Forgotten Inventor Who Helped Clean Up America’s Cities

Tomb of Queen Nefertari in the Valley of the Queens, Egypt

Discover the Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera

Venus de Losange: Unveiling the Mystery of a 20,000-Year-Old Paleolithic Icon