The Recarved Pharaoh: A Story of Power, Memory, and Reinvention in Ancient Egypt

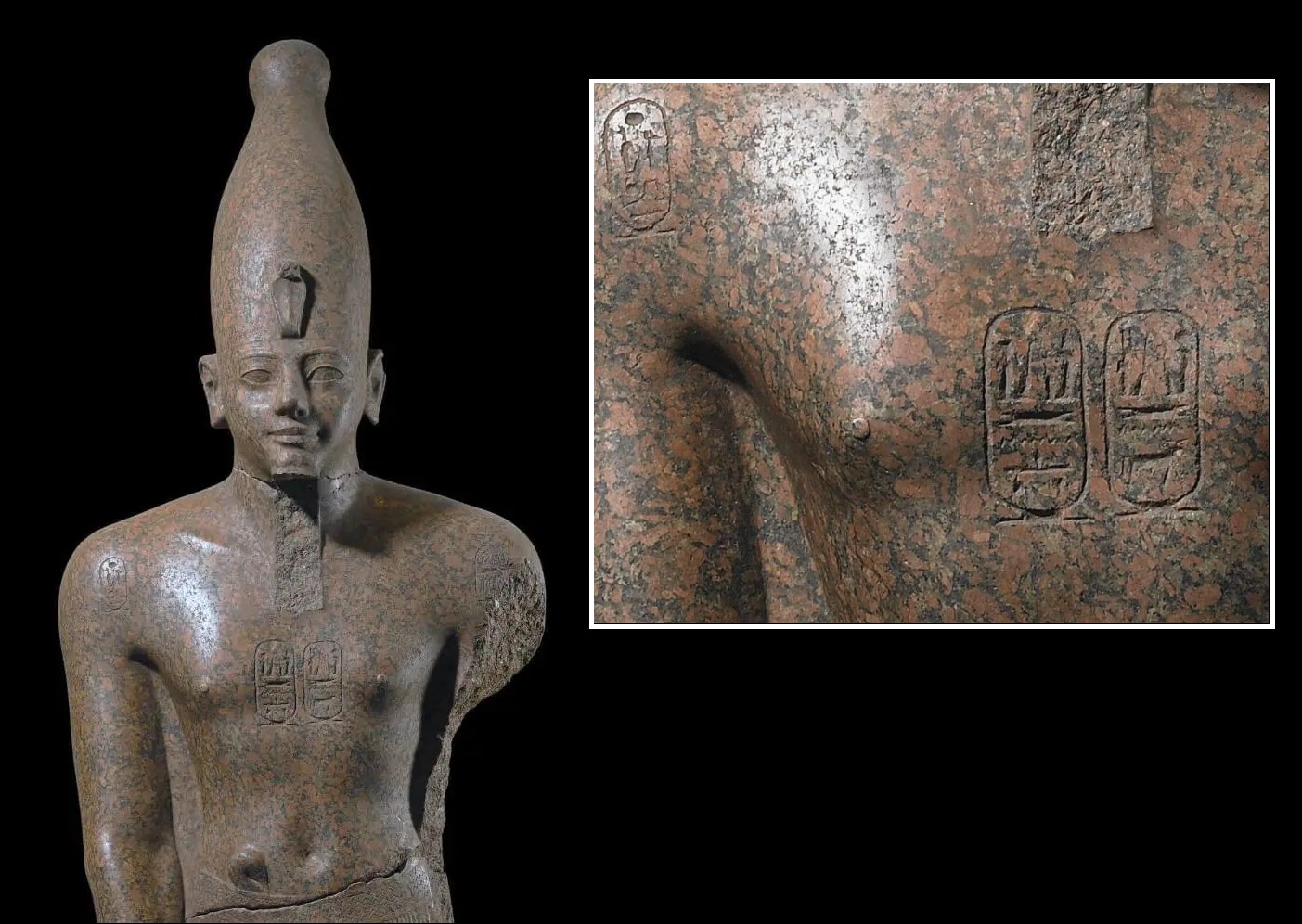

It stands in the British Museum today, quiet and commanding. A red granite statue of a king, wearing the tall White Crown of Upper Egypt. To most, it looks like a tribute to one of Egypt’s formidable Ramesside rulers—perhaps Ramesses II himself, the pharaoh whose monuments pepper the Nile from Luxor to Abu Simbel. But look again. Beneath the surface lies a tale far older, and far more complex.

A Closer Look: Tracing the Layers of Legacy

Catalogued as EA61, this statue was once part of the sprawling temple complex of Karnak. Its inscriptions tell us it was claimed by Ramesses II, and later by his son Merenptah. But the art itself whispers a different name.

Scholars, trained in the visual language of Egyptian statuary—the tilt of the head, the curve of the lips, the subtle way a brow is chiseled—believe this statue was originally made for Thutmose III, the warrior pharaoh of the 18th Dynasty. The facial features, proportions, and craftsmanship belong unmistakably to an earlier age, centuries before Ramesses ever ascended the throne.

And that’s where the story begins.

The Pharaoh Who Wrote Himself Into History

Ramesses II didn’t simply inherit Egypt—he reshaped its memory. Rather than commission new statues and temples for every occasion, he often took those of his royal predecessors and quite literally recut them to bear his own name. It was more than practical. It was political theater.

In a culture where memory was sacred and forgetting was a kind of death, usurping a statue meant rewriting the past to serve the present. To erase, overwrite, and absorb. Ramesses was not just claiming stone—he was claiming legacy.

He wasn’t the first to do so, but he was a master of the craft. When he placed his cartouche over that of Thutmose III, he wasn’t merely honoring a legendary predecessor—he was binding himself to a golden age of Egyptian power and projecting that glory into his own time.

Thutmose III: The Pharaoh Worth Emulating

Why Thutmose III? Because if there was ever a king worth invoking, it was him.

Often called the Napoleon of Ancient Egypt, Thutmose III ruled during one of the empire’s most expansive periods. His military campaigns—seventeen known expeditions—pushed Egyptian power deep into the Levant and secured wealth, tribute, and loyalty from foreign lands. He was a tactician, a builder, and a deeply pious man who maintained the traditions of the gods even as he expanded the empire’s borders.

He was also the heir of a powerful matriarchal legacy. His stepmother and co-regent, Hatshepsut, had ruled Egypt as king in her own right, presiding over a time of peace and artistic flowering. Thutmose eventually took full power and carved out a legacy that generations of pharaohs would revere.

And yet, that dynasty would not last forever.

After the Thutmosids: Collapse and Restoration

The 18th Dynasty, for all its glories, unraveled in the wake of Akhenaten’s religious revolution. His radical shift toward monotheism—worshiping the Aten above all—shattered Egypt’s priesthood and political traditions. After his brief and controversial reign, a boy-king named Tutankhamun tried to restore the old ways. But with his early death, the royal line of Thutmose came to an end.

What followed was an era of generals. Horemheb, once a commander under Tutankhamun, seized the throne not by birth but by merit. In doing so, he ushered in a new order—one rooted in military authority rather than divine lineage.

From Horemheb’s reforms emerged the Ramesside line. The kings who followed, including Ramesses I, Seti I, and the great Ramesses II, understood that to solidify their claim, they had to invoke the memory of Egypt’s past grandeur. And so they looked backward—to Thutmose, to Hatshepsut, even to gods long sidelined—to legitimize the present.

Stone as Memory: The Meaning Behind the Recarved Statue

This statue, then, is no ordinary monument. It is a palimpsest—an object that carries the ghost of a former identity beneath its surface. Carved for a warrior-king, repurposed by another, it is a silent witness to the ebb and flow of Egyptian history.

Its reuse wasn’t deception—it was homage and assertion. Ramesses II wasn’t trying to erase Thutmose III; he was claiming his mantle, aligning himself with an era of conquest and cosmic order. And in doing so, he ensured that both names—his and Thutmose’s—would live on, fused into a single story told in stone.

A Statue That Still Speaks

Today, in the galleries of the British Museum, this red granite figure still towers, enigmatic and proud. Visitors pass by, drawn to its regal posture and timeless gaze. Few realize that they are not just looking at a work of art—they are standing before a centuries-long dialogue between two of Egypt’s greatest kings.

In its silence, the statue speaks. Of ambition. Of continuity. Of how, in ancient Egypt, power was not only seized—it was remembered, repurposed, and recarved.

CÁC TIN KHÁC

Mary Walton: The Forgotten Inventor Who Helped Clean Up America’s Cities

Tomb of Queen Nefertari in the Valley of the Queens, Egypt

Discover the Hypostyle Hall of the Temple of Hathor at Dendera

Venus de Losange: Unveiling the Mystery of a 20,000-Year-Old Paleolithic Icon